160 160 | 1991 by Jason Dykes and David Unwin

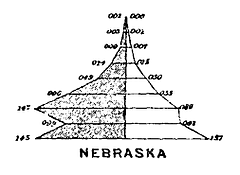

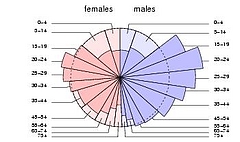

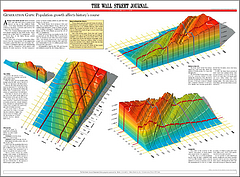

There are many difficulties in showing rates of incidence or proportions in maps, when both the areas of geographic regions, and the populations in those regions vary, often inversely. In spatial epidemiology, for example, Standardized Mortality Ratios are often used, expressing the ratios of the number of deaths in each area to those expected on the basis of some externally specified (typically national) age-sex specific rates.

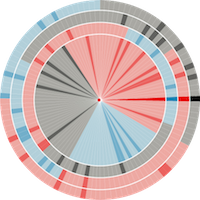

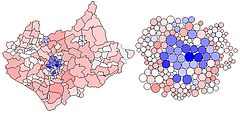

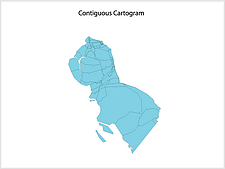

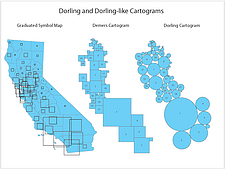

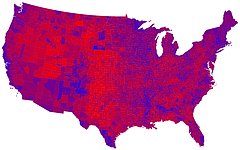

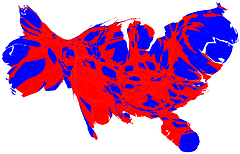

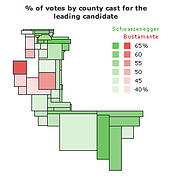

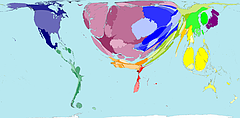

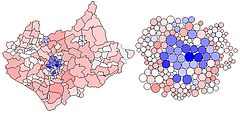

This figure uses a Chi-square metric to depict the distribution of number of cars, O, in each ward in Leicestershire, UK, expressed as a signed chi-square contribution, (Oi - Ei)/ Ö Ei, relative to the expected number, E, per capita. A diverging colour scheme applies hues of red and blue to those areas with higher and lower than expected values with colour saturation showing the magnitude of the variation. Thus whiter zones are close to the expected value and deeper blues and fuller reds show the extremes. This map still confounds area and population with visual impact, which the use of a cartogram base, with circle areas proportional to the population, helps avoid.

Figures from Maps of the Census: A Rough Guide, by Jason Dykes and David Unwin (http://www.agocg.ac.uk/reports/visual/casestud/dykes/abstra_1.htm).

Abstract:

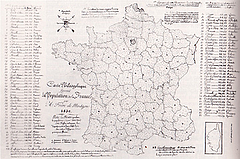

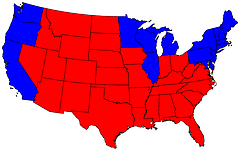

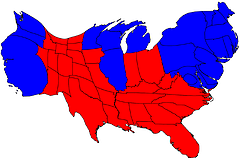

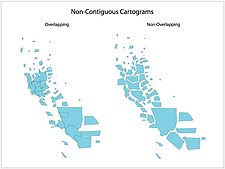

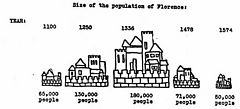

This Case Study describes the considerations that are needed to produce maps of data from the Census of Population. The `area value' or choropleth map is the standard means of displaying such information on paper. It is a very imperfect visualisation device. First, it is necessary to be careful about the numbers that are mapped and, in particular, never to map absolute numbers. Second, choropleth maps are very sensitive to the mapping zones being used. To produce maps that do not distort the underlying distributions it is necessary to understand how the zones were defined and the effects of their varying sizes on the mapped pattern. Third, there are a series of strictly cartographic considerations related to how these maps are classed and the symbolism used. All of these issues are illustrated using data from the 1991 Population Census for Leicestershire, UK.

These problems lead to a consideration of the need to develop new mapping tools. Dynamic maps can take advantage of an interactive software environment to overcome some of the limitations of the static map. The possibilities which they provide for interactive engagement with data make them appropriate tools for exploratory analysis, or visual thinking. A mapping tool is introduced, which exemplifies this form of map use and examples of the techniques that might be used to visualize the UK Census of Population are provided.

|

542

542  750

750